SEMBLANZAS V. BOB DYLAN (TERCERA PARTE )

SEMBLANZAS V

BOB DYLAN

(TERCERA PARTE)

ADDENDUM: EL DISCURSO DEL NOBEL

Bob DYLAN Nobel Lecture

5 June 2017

When I first received this Nobel Prize for Literature,

I got to wondering exactly how my songs related to literature. I wanted to

reflect on it and see where the connection was. I'm going to try to articulate

that to you. And most likely it will go in a roundabout way, but I hope what I

say will be worthwhile and purposeful.

If I was to go back to the dawning of it all, I guess

I'd have to start with Buddy Holly. Buddy died when I was about eighteen and he

was twenty-two. From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related,

like he was an older brother. I even thought I resembled him. Buddy played the

music that I loved – the music I grew up on: country western, rock ‘n' roll,

and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and

infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs – songs that had

beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great – sang in more

than a few voices. He was the archetype. Everything I wasn't and wanted to be.

I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone. I had to

travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn't disappointed.

He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding

presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his

hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the

glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit.

Everything about him. He looked older than twenty-two. Something about him

seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the

most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and

he transmitted something. Something I didn't know what. And it gave me the

chills.

I think it was a day or two after that that his plane

went down. And somebody – somebody I'd never seen before – handed me a

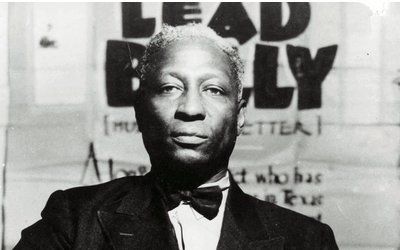

Leadbelly record with the song "Cottonfields" on it. And that record

changed my life right then and there. Transported me into a world I'd never

known. It was like an explosion went off. Like I'd been walking in darkness and

all of the sudden the darkness was illuminated. It was like somebody laid hands

on me. I must have played that record a hundred times.

It was on a label I'd never heard of with a booklet

inside with advertisements for other artists on the label: Sonny Terry and

Brownie McGhee, the New Lost City Ramblers, Jean Ritchie, string bands. I'd

never heard of any of them. But I reckoned if they were on this label with

Leadbelly, they had to be good, so I needed to hear them. I wanted to know all

about it and play that kind of music. I still had a feeling for the music I'd

grown up with, but for right now, I forgot about it. Didn't even think about

it. For the time being, it was long gone.

I hadn't left home yet, but I couldn't wait to. I

wanted to learn this music and meet the people who played it. Eventually, I did

leave, and I did learn to play those songs. They were different than the radio

songs that I'd been listening to all along. They were more vibrant and truthful

to life. With radio songs, a performer might get a hit with a roll of the dice

or a fall of the cards, but that didn't matter in the folk world. Everything

was a hit. All you had to do was be well versed and be able to play the melody.

Some of these songs were easy, some not. I had a natural feeling for the

ancient ballads and country blues, but everything else I had to learn from

scratch. I was playing for small crowds, sometimes no more than four or five

people in a room or on a street corner. You had to have a wide repertoire, and

you had to know what to play and when. Some songs were intimate, some you had

to shout to be heard.

By listening to all the early folk artists and singing

the songs yourself, you pick up the vernacular. You internalize it. You sing it

in the ragtime blues, work songs, Georgia sea shanties, Appalachian ballads and

cowboy songs. You hear all the finer points, and you learn the details.

You know what it's all about. Takin' the pistol out

and puttin' it back in your pocket. Whippin' your way through traffic, talkin'

in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a

good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you've heard the

deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a

boggy creek. And you're pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial

boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You've seen

the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades

have been wrapped in white linen.

I had all the vernacular down. I knew the rhetoric.

None of it went over my head – the devices, the techniques, the secrets, the

mysteries – and I knew all the deserted roads that it traveled on, too. I could

make it all connect and move with the current of the day. When I started

writing my own songs, the folk lingo was the only vocabulary that I knew, and I

used it.

But I had something else as well. I had principles and

sensibilities and an informed view of the world. And I had had that for a

while. Learned it all in grammar school. Don

Quixote, Ivanhoe,

Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels, Tale of Two Cities, all

the rest – typical grammar school reading that gave you a way of looking at

life, an understanding of human nature, and a standard to measure things by. I

took all that with me when I started composing lyrics. And the themes from

those books worked their way into many of my songs, either knowingly or

unintentionally. I wanted to write songs unlike anything anybody ever heard,

and these themes were fundamental.

Specific books that have stuck with me ever since I

read them way back in grammar school – I want to tell you about three of them: Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western

Front and The Odyssey.

Moby Dick is a fascinating book, a book that's filled with scenes of high drama and dramatic dialogue. The book makes demands on you. The plot is straightforward. The mysterious Captain Ahab – captain of a ship called the Pequod – an egomaniac with a peg leg pursuing his nemesis, the great white whale Moby Dick who took his leg. And he pursues him all the way from the Atlantic around the tip of Africa and into the Indian Ocean. He pursues the whale around both sides of the earth. It's an abstract goal, nothing concrete or definite. He calls Moby the emperor, sees him as the embodiment of evil. Ahab's got a wife and child back in Nantucket that he reminisces about now and again. You can anticipate what will happen.

The ship's crew is made up of men of different races,

and any one of them who sights the whale will be given the reward of a gold

coin. A lot of Zodiac symbols, religious allegory, stereotypes. Ahab encounters

other whaling vessels, presses the captains for details about Moby. Have they

seen him? There's a crazy prophet, Gabriel, on one of the vessels, and he

predicts Ahab's doom. Says Moby is the incarnate of a Shaker god, and that any

dealings with him will lead to disaster. He says that to Captain Ahab. Another

ship's captain – Captain Boomer – he lost an arm to Moby. But he tolerates

that, and he's happy to have survived. He can't accept Ahab's lust for

vengeance.

This book tells how different men react in different

ways to the same experience. A lot of Old Testament, biblical allegory:

Gabriel, Rachel, Jeroboam, Bildah, Elijah. Pagan names as well: Tashtego,

Flask, Daggoo, Fleece, Starbuck, Stubb, Martha's Vineyard. The Pagans are idol

worshippers. Some worship little wax figures, some wooden figures. Some worship

fire. The Pequod is the name of an Indian tribe.

Moby Dick is a seafaring tale. One of the men, the narrator,

says, "Call me Ishmael." Somebody asks him where he's from, and he

says, "It's not down on any map. True places never are." Stubb gives

no significance to anything, says everything is predestined. Ishmael's been on

a sailing ship his entire life. Calls the sailing ships his Harvard and Yale.

He keeps his distance from people.

A typhoon hits the Pequod. Captain Ahab thinks it's a

good omen. Starbuck thinks it's a bad omen, considers killing Ahab. As soon as

the storm ends, a crewmember falls from the ship's mast and drowns,

foreshadowing what's to come. A Quaker pacifist priest, who is actually a

bloodthirsty businessman, tells Flask, "Some men who receive injuries are

led to God, others are led to bitterness."

Everything is mixed in. All the myths: the Judeo

Christian bible, Hindu myths, British legends, Saint George, Perseus, Hercules

– they're all whalers. Greek mythology, the gory business of cutting up a

whale. Lots of facts in this book, geographical knowledge, whale oil – good for

coronation of royalty – noble families in the whaling industry. Whale oil is

used to anoint the kings. History of the whale, phrenology, classical

philosophy, pseudo-scientific theories, justification for discrimination –

everything thrown in and none of it hardly rational. Highbrow, lowbrow, chasing

illusion, chasing death, the great white whale, white as polar bear, white as a

white man, the emperor, the nemesis, the embodiment of evil. The demented

captain who actually lost his leg years ago trying to attack Moby with a knife.

We see only the surface of things. We can interpret

what lies below any way we see fit. Crewmen walk around on deck listening for

mermaids, and sharks and vultures follow the ship. Reading skulls and faces

like you read a book. Here's a face. I'll put it in front of you. Read it if

you can.

Tashtego says that he died and was reborn. His extra

days are a gift. He wasn't saved by Christ, though, he says he was saved by a

fellow man and a non-Christian at that. He parodies the resurrection.

When Starbuck tells Ahab that he should let bygones be

bygones, the angry captain snaps back, "Speak not to me of blasphemy, man,

I'd strike the sun if it insulted me." Ahab, too, is a poet of eloquence.

He says, "The path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails whereon my

soul is grooved to run." Or these lines, "All visible objects

are but pasteboard masks." Quotable poetic phrases that can't be

beat.

Finally, Ahab spots Moby, and the harpoons come out.

Boats are lowered. Ahab's harpoon has been baptized in blood. Moby attacks

Ahab's boat and destroys it. Next day, he sights Moby again. Boats are lowered

again. Moby attacks Ahab's boat again. On the third day, another boat goes in.

More religious allegory. He has risen. Moby attacks one more time, ramming the

Pequod and sinking it. Ahab gets tangled up in the harpoon lines and is thrown

out of his boat into a watery grave.

Ishmael survives. He's in the sea floating on a

coffin. And that's about it. That's the whole story. That theme and all that it

implies would work its way into more than a few of my songs.

All Quiet on the Western Front was another book that did. All Quiet on the Western Front is a horror story. This is a book where you lose your childhood, your faith in a meaningful world, and your concern for individuals. You're stuck in a nightmare. Sucked up into a mysterious whirlpool of death and pain. You're defending yourself from elimination. You're being wiped off the face of the map. Once upon a time you were an innocent youth with big dreams about being a concert pianist. Once you loved life and the world, and now you're shooting it to pieces.

Day after day, the hornets bite you and worms lap your

blood. You're a cornered animal. You don't fit anywhere. The falling rain is

monotonous. There's endless assaults, poison gas, nerve gas, morphine, burning

streams of gasoline, scavenging and scabbing for food, influenza, typhus,

dysentery. Life is breaking down all around you, and the shells are whistling.

This is the lower region of hell. Mud, barbed wire, rat-filled trenches, rats

eating the intestines of dead men, trenches filled with filth and excrement.

Someone shouts, "Hey, you there. Stand and fight."

Who knows how long this mess will go on? Warfare has

no limits. You're being annihilated, and that leg of yours is bleeding too

much. You killed a man yesterday, and you spoke to his corpse. You told him

after this is over, you'll spend the rest of your life looking after his

family. Who's profiting here? The leaders and the generals gain fame, and many

others profit financially. But you're doing the dirty work. One of your

comrades says, "Wait a minute, where are you going?" And you say,

"Leave me alone, I'll be back in a minute." Then you walk out into

the woods of death hunting for a piece of sausage. You can't see how anybody in

civilian life has any kind of purpose at all. All their worries, all their

desires – you can't comprehend it.

More machine guns rattle, more parts of bodies hanging

from wires, more pieces of arms and legs and skulls where butterflies perch on

teeth, more hideous wounds, pus coming out of every pore, lung wounds, wounds

too big for the body, gas-blowing cadavers, and dead bodies making retching

noises. Death is everywhere. Nothing else is possible. Someone will kill you

and use your dead body for target practice. Boots, too. They're your prized

possession. But soon they'll be on somebody else's feet.

There's Froggies coming through the trees. Merciless

bastards. Your shells are running out. "It's not fair to come at us again

so soon," you say. One of your companions is laying in the dirt, and you

want to take him to the field hospital. Someone else says, "You might save

yourself a trip." "What do you mean?" "Turn him over,

you'll see what I mean."

You wait to hear the news. You don't understand why

the war isn't over. The army is so strapped for replacement troops that they're

drafting young boys who are of little military use, but they're draftin' ‘em

anyway because they're running out of men. Sickness and humiliation have broken

your heart. You were betrayed by your parents, your schoolmasters, your

ministers, and even your own government.

The general with the slowly smoked cigar betrayed you

too – turned you into a thug and a murderer. If you could, you'd put a bullet

in his face. The commander as well. You fantasize that if you had the money,

you'd put up a reward for any man who would take his life by any means

necessary. And if he should lose his life by doing that, then let the money go

to his heirs. The colonel, too, with his caviar and his coffee – he's another

one. Spends all his time in the officers' brothel. You'd like to see him stoned

dead too. More Tommies and Johnnies with their whack fo' me daddy-o and their

whiskey in the jars. You kill twenty of ‘em and twenty more will spring up in

their place. It just stinks in your nostrils.

You've come to despise that older generation that sent

you out into this madness, into this torture chamber. All around you, your

comrades are dying. Dying from abdominal wounds, double amputations, shattered

hipbones, and you think, "I'm only twenty years old, but I'm capable of

killing anybody. Even my father if he came at me."

Yesterday, you tried to save a wounded messenger dog, and somebody shouted, "Don't be a fool." One Froggy is laying gurgling at your feet. You stuck him with a dagger in his stomach, but the man still lives. You know you should finish the job, but you can't. You're on the real iron cross, and a Roman soldier's putting a sponge of vinegar to your lips.

Yesterday, you tried to save a wounded messenger dog, and somebody shouted, "Don't be a fool." One Froggy is laying gurgling at your feet. You stuck him with a dagger in his stomach, but the man still lives. You know you should finish the job, but you can't. You're on the real iron cross, and a Roman soldier's putting a sponge of vinegar to your lips.

Months pass by. You go home on leave. You can't

communicate with your father. He said, "You'd be a coward if you don't

enlist." Your mother, too, on your way back out the door, she says,

"You be careful of those French girls now." More madness. You fight

for a week or a month, and you gain ten yards. And then the next month it gets

taken back.

All that culture from a thousand years ago, that

philosophy, that wisdom – Plato, Aristotle, Socrates – what happened to it?

It should have prevented this. Your thoughts turn homeward. And once

again you're a schoolboy walking through the tall poplar trees. It's a pleasant

memory. More bombs dropping on you from blimps. You got to get it together now.

You can't even look at anybody for fear of some miscalculable thing that might

happen. The common grave. There are no other possibilities.

Then you notice the cherry blossoms, and you see that

nature is unaffected by all this. Poplar trees, the red butterflies, the

fragile beauty of flowers, the sun – you see how nature is indifferent to it

all. All the violence and suffering of all mankind. Nature doesn't even notice

it.

You're so alone. Then a piece of shrapnel hits the

side of your head and you're dead.

You've been ruled out, crossed out. You've been exterminated. I put this book down and closed it up. I never wanted to read another war novel again, and I never did.

You've been ruled out, crossed out. You've been exterminated. I put this book down and closed it up. I never wanted to read another war novel again, and I never did.

Charlie Poole from North Carolina had a song that

connected to all this. It's called "You Ain't Talkin' to Me," and the

lyrics go like this:

I saw a sign in a window walking up town one day.

Join the army, see the world is what it had to say.

You'll see exciting places with a jolly crew,

You'll meet interesting people, and learn to kill them too.

Oh you ain't talkin' to me, you ain't talking to me.

I may be crazy and all that, but I got good sense you see.

You ain't talkin' to me, you ain't talkin' to me.

Killin' with a gun don't sound like fun.

You ain't talkin' to me.

Join the army, see the world is what it had to say.

You'll see exciting places with a jolly crew,

You'll meet interesting people, and learn to kill them too.

Oh you ain't talkin' to me, you ain't talking to me.

I may be crazy and all that, but I got good sense you see.

You ain't talkin' to me, you ain't talkin' to me.

Killin' with a gun don't sound like fun.

You ain't talkin' to me.

The Odyssey is a great book whose themes have worked its way into the ballads of a lot of songwriters: "Homeward Bound, "Green, Green Grass of Home," "Home on the Range," and my songs as well.

The Odyssey is a strange, adventurous tale of a grown man trying

to get home after fighting in a war. He's on that long journey home, and it's

filled with traps and pitfalls. He's cursed to wander. He's always getting

carried out to sea, always having close calls. Huge chunks of boulders rock his

boat. He angers people he shouldn't. There's troublemakers in his crew.

Treachery. His men are turned into pigs and then are turned back into younger,

more handsome men. He's always trying to rescue somebody. He's a travelin' man,

but he's making a lot of stops.

He's stranded on a desert island. He finds deserted

caves, and he hides in them. He meets giants that say, "I'll eat you

last." And he escapes from giants. He's trying to get back home, but he's

tossed and turned by the winds. Restless winds, chilly winds, unfriendly winds.

He travels far, and then he gets blown back.

He's always being warned of things to come. Touching

things he's told not to. There's two roads to take, and they're both bad. Both

hazardous. On one you could drown and on the other you could starve. He goes

into the narrow straits with foaming whirlpools that swallow him. Meets

six-headed monsters with sharp fangs. Thunderbolts strike at him. Overhanging

branches that he makes a leap to reach for to save himself from a raging river.

Goddesses and gods protect him, but some others want to kill him. He changes

identities. He's exhausted. He falls asleep, and he's woken up by the sound of

laughter. He tells his story to strangers. He's been gone twenty years. He was

carried off somewhere and left there. Drugs have been dropped into his wine.

It's been a hard road to travel.

In a lot of ways, some of these same things have

happened to you. You too have had drugs dropped into your wine. You too have

shared a bed with the wrong woman. You too have been spellbound by magical

voices, sweet voices with strange melodies. You too have come so far and have

been so far blown back. And you've had close calls as well. You have angered

people you should not have. And you too have rambled this country all around.

And you've also felt that ill wind, the one that blows you no good. And that's

still not all of it.

When he gets back home, things aren't any better.

Scoundrels have moved in and are taking advantage of his wife's hospitality.

And there's too many of ‘em. And though he's greater than them all and the best

at everything – best carpenter, best hunter, best expert on animals, best

seaman – his courage won't save him, but his trickery will.

All these stragglers will have to pay for desecrating

his palace. He'll disguise himself as a filthy beggar, and a lowly servant

kicks him down the steps with arrogance and stupidity. The servant's arrogance

revolts him, but he controls his anger. He's one against a hundred, but they'll

all fall, even the strongest. He was nobody. And when it's all said and done,

when he's home at last, he sits with his wife, and he tells her the stories.

So what does it all mean? Myself and a lot of other songwriters have been influenced by these very same themes. And they can mean a lot of different things. If a song moves you, that's all that's important. I don't have to know what a song means. I've written all kinds of things into my songs. And I'm not going to worry about it – what it all means. When Melville put all his old testament, biblical references, scientific theories, Protestant doctrines, and all that knowledge of the sea and sailing ships and whales into one story, I don't think he would have worried about it either – what it all means.

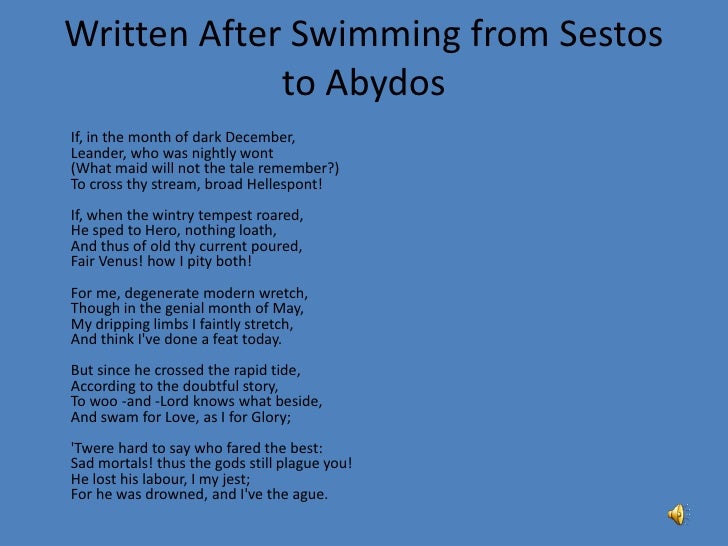

John Donne as well, the poet-priest who lived in the

time of Shakespeare, wrote these words, "The Sestos and Abydos of her

breasts. Not of two lovers, but two loves, the nests." I don't know what

it means, either. But it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good.

When Odysseus in The

Odyssey visits the famed warrior Achilles in the underworld –

Achilles, who traded a long life full of peace and contentment for a short one

full of honor and glory – tells Odysseus it was all a mistake. "I

just died, that's all." There was no honor. No immortality. And that if he

could, he would choose to go back and be a lowly slave to a tenant farmer on

Earth rather than be what he is – a king in the land of the dead – that

whatever his struggles of life were, they were preferable to being here in this

dead place.

That's what songs are too. Our songs are alive in the

land of the living. But songs are unlike literature. They're meant to be sung,

not read. The words in Shakespeare's plays were meant to be acted on the stage.

Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page. And I hope

some of you get the chance to listen to these lyrics the way they were intended

to be heard: in concert or on record or however people are listening to songs

these days. I return once again to Homer, who says, "Sing in me, oh Muse,

and through me tell the story."

06.06.2017 – 09:10 H. TRADUCCIÓN (no revisada)

Bob Dylan ya ha enviado

a la Academia Sueca su discurso de aceptación del premio Nobel de Literatura, un trámite necesario para recibir el premio en

efectivo según el reglamento, por lo que podrá ingresar finalmente los ocho

millones de coronas suecas (819.000

euros).

Este es el discurso:

"Cuando supe que había obtenido el Premio Nobel,

me surgió la pregunta de cómo se

relacionaban exactamente mis canciones con la literatura. Quise

reflexionar sobre ello y ver dónde se hallaba la conexión. Voy a tratar de

articularlo. Y lo más probable es que lo haga dando rodeos, pero espero que lo

que diga valga la pena y tenga sentido.

Si tuviera que volver al amanecer de todo, creo que

tendría que empezar con Buddy

Holly. Buddy murió cuando yo tenía dieciocho años y él

veintidós. Desde el momento en que lo escuché por primera vez, me sentí

identificado. Sentí casi que era como un hermano mayor. Hasta pensé que me

parecía a él. Buddy tocaba la música que me apasionaba -la música con la que

crecí: country western, rock 'n' roll y rhythm&blues-. Tres hebras

separadas de la música que entrelazó y fundió en un género. Una marca. Y Buddy

escribía canciones - canciones que tenían bellas melodías y versos

imaginativos. Y cantaba muy bien - cantaba

con distintas voces. Él era el arquetipo. Todo lo que yo

no era y quería ser. Lo vi sólo una vez, unos días antes de su muerte. Tuve que

viajar 100 millas para verlo actuar y no me decepcionó.

Era poderoso y electrizante y tenía una presencia

imponente. Yo estaba a solo seis pies de distancia. Estaba hipnotizado. Le miré

la cara, las manos, la forma en que marcaba el ritmo con el pie, sus grandes

gafas negras, los ojos detrás de las gafas, la forma en que sostenía su

guitarra, su postura, su traje elegante. Todo él. Aparentaba más de veintidós

años. Algo en él parecía permanente, y me llenó de convicción. Entonces, de

repente, sucedió lo más extraño. Me miró directamente a los ojos y me transmitió

algo. Algo que no sé lo que era. Y sentí escalofríos.

Creo que fue un día o dos después de que su avión se

estrellara. Y alguien -alguien a quien nunca había visto- me dio un disco de

Leadbelly que incluía la canción 'Cottonfields'. Y este disco cambió mi vida en

ese momento y en ese lugar. Me transportó a un mundo desconocido. Fue como una

explosión. Como si hubiera estado caminando en la oscuridad y, de repente, la

oscuridad se iluminara. Era como si alguien hubiera puesto sus manos en mí.

Debo de haber tocado esa canción cientos de veces.

Estaba en un sello discográfico del que nunca había

oído hablar con un libreto dentro lleno de anuncios de otros artistas del

sello: Sonny Terry y Brownie McGhee, The New Lost City Ramblers, Jean Ritchie,

'string bands'. Nunca había oído hablar de ninguno de ellos. Pero consideré que

si estaban en esta etiqueta con Leadbelly, tenían que ser buenos, así que

necesitaba escucharlos. Quería saberlo todo y tocar ese tipo de música. Todavía

me atraía la música con la que había crecido pero, de pronto, se me olvidó. Ni

siquiera lo pensé. En ese momento, hacía tiempo que esa música había

desaparecido.

Todavía no me había ido de casa, pero estaba ansioso:

quería conocer esa música y a la gente que la tocaba. Al final me marché del hogar

y aprendí a tocar esas canciones. Eran diferentes de las canciones que ponían

en la radio y que había estado escuchando hasta entonces. Eran más vibrantes y

más sinceras. Con las canciones que suenan en la radio, un intérprete podría

conseguir el éxito como con una tirada de dados o una buena mano de cartas,

pero eso no importaba en el mundo del folk. Todo era un éxito. Todo lo que

tenías que hacer era escribir buenos versos y ser capaz de tocar una melodía.

Algunas de estas canciones eran fáciles, otras no. Tenía una predisposición

natural para las viejas baladas y el 'country blues', pero todo lo demás lo

tuve que aprender desde cero. Tocaba para un público pequeño, a veces de no más

de cuatro o cinco personas, en una habitación o en una esquina en la calle.

Había que tener un amplio repertorio, y tenías que saber qué tocar y cuándo

tocarlo. Algunas canciones eran intimistas, en algunas había que gritar para

que te escucharan.

Puedes aprender la jerga escuchando a los artistas

folk de los primeros años y cantando sus canciones. La interiorizas. La cantas

en los blues a tiempo rasgado, en las canciones de trabajo, en las canciones

que cantaban los marinos mercantes de Georgia, en las baladas de los Apalaches

y en las canciones de los 'cowboys'. Escuchas los matices y aprendes los

detalles.

Ya sabéis de qué va esto. De sacar la pistola y

volver a meterla en la pistolera. De abrirte camino a través del tráfico, de

hablar en la oscuridad. Ya sabéis que Stagger Lee era un mal tipo y que Frankie

era una buena chica. Ya sabéis que Washington es una ciudad burguesa y ya

habéis oído la voz profunda de John the Revelator y ya habéis visto al Titanic

hundirse en un arroyo cenagoso. Y sois colegas del vagabundo irlandés y del

chico de las colonias. Escuchasteis la batería amortiguada y los flauitines que

tocaban bajito. Habéis visto al lujurioso Lord Donald clavarle un cuchillo a su

mujer y a muchos de vuestros camaradas envueltos en lino blanco.

Pero yo también tenía algo más. Tenía principios y

sensibilidades y una visión informada del mundo. Y la había tenido desde hace

tiempo. Lo aprendí todo en la escuela primaria. Don Quijote, Ivanhoe, Robinson Crusoe, Los viajes de Gulliver, Historia

de dos ciudades, todo lo demás - lectura típica de la escuela secundaria que te

da una manera de ver la vida, una comprensión de la naturaleza humana y un

estándar para medir las cosas. Tomé todo eso conmigo cuando empecé a componer

letras. Y los temas de esos libros funcionaron en muchas de mis canciones, ya

sea a sabiendas o sin intención. Quería escribir canciones que fuesen

diferentes a cualquier cosa que alguien hubiera escuchado, y estos temas eran

fundamentales.

Algunos de los libros específicos que han permanecido

conmigo desde entonces, los había leído en la escuela secundaria. Quiero

hablarles de tres de ellos: 'Moby Dick', 'Sin novedad en el frente' y 'La

Odisea'.

'Moby Dick' es un libro

fascinante, un libro que está lleno de escenas y diálogos

dramáticos. El libro te exige. La trama es sencilla. El misterioso Ahab

-capitán de un barco llamado el Pequod- un egomaníaco con una pierna de perno

que persigue su némesis, la gran ballena blanca Moby Dick que se la arrancó. Y

la persigue desde el Atlántico, bordeando la punta de África y adentándose en

el Océano Índico. Persigue a la ballena de una punta a otra de la Tierra. Es un

objetivo abstracto, nada concreto o definido. Él la llama Moby el emperador, y

la ve como la encarnación del mal. Ahab tiene una esposa y un hijo en Nantucket

que recuerda de vez en cuando. Ya podéis imaginaros lo que acaba sucediendo.

La tripulación del buque está formada por hombres de

diferentes razas, y cualquiera que vea a la ballena recibirá la recompensa de

una moneda de oro. Una gran cantidad de símbolos del zodíaco, alegorías

religiosas, estereotipos. Cuando Ahab se encuentra con otros barcos balleneros,

presiona a los capitanes para obtener detalles sobre Moby. ¿Lo han visto? Hay

un profeta loco, Gabriel, que predice la condena de Ahab. Moby encarna al dios

Shaker y cualquier trato con él llevará al desastre. Se lo dice al capitán

Ahab. Otro capitán del buque, el Capitán Boomer, pierde un brazo contra Moby.

Pero él se aguanta y está feliz de haber sobrevivido. No puede aceptar la sed

de venganza de Ahab.

Este libro cuenta cómo los diferentes hombres

reaccionan de distintas maneras a la misma experiencia. Hay mucho del Antiguo

Testamento, mucha alegoría bíblica: Gabriel, Raquel, Jeroboam, Bildah, Elijah.

Nombres paganos también: Tashtego, Frasco, Daggoo, Fleece, Starbuck, Stubb,

Martha's Vineyard. Los paganos son adoradores de ídolos. Algunos adoran

pequeñas figuras de cera, algunas figuras de madera. Algunos adoran el fuego.

El Pequod es el nombre de una tribu india.

'Moby Dick' es un cuento marinero. Uno de los

hombres, el narrador, dice: "Llámame Ismael". Alguien le pregunta de

dónde viene, y él dice: "No está en ningún mapa. Los verdaderos lugares nunca lo están". Stubb

no da significado a nada, dice que todo está predestinado. Ismael ha estado en

un velero toda su vida. Llama a los veleros su Harvard y su Yale. Y mantiene su

distancia de la gente.

Un tifón golpea al Pequod. El capitán Ahab cree que

es un buen presagio. Starbuck, que piensa que es un mal presagio, considera

matar a Ahab. Tan pronto como la tormenta termina, un miembro de la tripulación

cae del mástil del barco y se ahoga, anticipando lo que está por venir. Un

sacerdote pacifista cuáquero, que en realidad es un hombre de negocios

sanguinario, le dice a Flask: "Algunos hombres heridos siguen el camino de

Dios, otros el camino de la amargura."

Todo está mezclado. Todos los mitos: la Biblia

judeo-cristiana, los mitos hindúes, las leyendas británicas, San Jorge, Perseo,

Hércules, todos ellos son balleneros. La mitología griega, el negocio

sanguinario de cortar una ballena. Muchos hechos en este libro, como

conocimientos geográficos, el aceite de ballena -bueno para la coronación de la

realeza- familias nobles en la industria ballenera... El aceite de ballena se

usa para ungir a los reyes. La historia de la ballena, frenología, filosofía

clásica, teorías pseudocientíficas, justificación de la discriminación, todo

incluido y nada racional. Ilustres, persiguiendo la ilusión, persiguiendo la

muerte, la gran ballena blanca, blanca como el oso polar, blanca como un hombre

blanco, el emperador, la némesis, la encarnación del mal. El capitán demente

que en realidad perdió su pierna hace años tratando de atacar a Moby con un

cuchillo.

Solo vemos la superficie de las cosas. Podemos interpretar

lo que está debajo de cualquier forma que creamos conveniente. Los tripulantes

caminan en la cubierta escuchando las sirenas, y los tiburones y los buitres

persiguen la nave. Leer los cráneos y las caras como usted lee un libro. Aquí

hay una cara. Lo pondré delante de usted. Léalo si puede.

Tashtego dice que murió y renació. Sus días extra son

un regalo. No fue salvado por Cristo, sin embargo, dice que fue salvo por un

compañero: un no cristiano. Una parodia de la resurrección.

Cuando Starbuck le dice a Ahab que debe pasar página,

el capitán enojado le responde: "No me hables de blasfemia, hombre, porque

sería capaz de golpear al sol si me insultara". Ahab, también, es un poeta

de la elocuencia. Él dice: "El camino hacia mi propósito fijo está puesto

con rieles de hierro sobre los cuales mi alma está diseñada para rodar". O

estas líneas: "Todos los objetos visibles son máscaras de cartón".

Frases poéticas que no pueden mejorarse.

Finalmente, Ahab ve a Moby y aparecen los arpones.

Los barcos se vacían. El arpón de Ahab ha sido bautizado en sangre. Moby ataca

el barco de Ahab y lo destruye. Al día siguiente, vuelve a avistar a Moby. Los

barcos se vacían de nuevo. Moby ataca de nuevo el barco de Ahab. Al tercer día,

otro barco entra. Más alegoría religiosa. Se ha elevado. Moby ataca una vez

más, golpeando al Pequod y hundiéndolo. Ahab se enreda en las cuerdas del arpón

y cae de su barco a una tumba acuosa.

Ismael sobrevive. Está en el mar flotando en un

ataúd. Y eso es todo. Esa es toda la historia. Ese tema y todo lo que implica

funcionaría en más de una de mis canciones.

'Sin novedad en el frente' era otro libro que también

encajaría en mis canciones. 'Sin novedad en el frente' es una historia de

terror. Este es un libro donde pierdes tu infancia, tu fe en un mundo con

sentido, y tu interés por los individuos. Estás atrapado en una pesadilla.

Sumergido en un misterioso remolino de muerte y dolor. Te estás defendiendo de

la eliminación. Te van a borrar de la faz del mapa. Había una vez un joven

inocente con grandes sueños de ser concertista. Hace un momento amabas la vida

y el mundo, y ahora estás disparando.

Día tras día, las avispas te muerden y los gusanos

recorren tu sangre. Eres un animal acorralado. No encajas en ninguna parte. La

lluvia que cae es monótona. Hay interminables asaltos, gas venenoso, gas

nervioso, morfina, corrientes ardientes de gasolina, barrido y escabechado de

alimentos, gripe, tifus, disentería. La vida se derrumba a tu alrededor, y las

conchas están silbando. Esta es la región inferior del infierno. Barro, alambre

de púas, trincheras llenas de ratas, ratas comiendo intestinos de hombres

muertos, trincheras llenas de suciedad y excrementos. Alguien grita: "Eh,

tú ahí. Párate y pelea."

¿Quién sabe cuánto tiempo durará este lío? La guerra

no tiene límites. Te están aniquilando, y esa pierna está sangrando demasiado.

Ayer mataste a un hombre y hablabas con su cadáver. Le dijiste que después de

que esto haya terminado, pasarás el resto de tu vida cuidando a su familia.

¿Quién se beneficia aquí? Los líderes y los generales ganan fama, y muchos

otros se benefician financieramente. Pero tú estás haciendo el trabajo sucio.

Uno de tus camaradas dice: "Espera un momento, ¿a dónde vas?" Y tú

dices: "Déjame en paz, volveré en un minuto". Entonces entras en el

bosque de la muerte buscando un pedazo de salchicha. No puedes entender que los

civiles puedan tener algún tipo de propósito en la vida. Todas sus

preocupaciones, todos sus deseos - no puedes comprenderlo.

Más ametralladoras atronadoras, más partes de cuerpos

que cuelgan de los alambres, más piezas de brazos y piernas y cráneos donde las

mariposas se posan en los dientes, heridas más espantosas, pus saliendo de cada

poro, heridas de pulmón, heridas demasiado grandes para el cuerpo, cadáveres que

sueltan gas y cuerpos muertos haciendo ruidos vomitivos. La muerte está en

todas partes. Nada más es posible. Alguien te matará y usará tu cadáver para

practicar tiro. Botas, también. Son tu posesión más preciada. Pero pronto

estarán en los pies de otra persona.

Hay soldados que atraviesan los árboles. Cabrones

despiadados. Te estás quedando sin balas. "No es justo que nos ataquen

otra vez tan pronto", dices. Uno de tus compañeros está tendido en la

tierra, y quieres llevarlo al hospital de campaña. Alguien más dice:

"Podrías ahorrarte un viaje." "¿Qué quieres decir?"

"Gíralo, verás lo que quiero decir."

Esperas a oír las noticias. No entiendes por qué la

guerra no ha terminado. El ejército está tan corto de tropas de reemplazo que

están reclutando a muchachos sin formación militar porque se están quedando sin

hombres. La enfermedad y la humillación han roto tu corazón. Tus padres te han

traicionado, tus maestros de escuela, tus ministros, e incluso tu propio

gobierno.

El general que fuma un cigarro lentamente te

traicionó también -te convirtió en un matón y un asesino. Si pudieras, le

meterías un balazo en la cara. El comandante también. Fantaseas con que si

tuvieses el dinero, ofrecerías una recompensa para cualquier hombre que le

quitase la vida por un módico precio. Y si a él lo matasen, aun así tendría

dinero para dejarles a sus herederos. El coronel también, con su caviar y su

café, otro más. Pasa todo su tiempo en el burdel de los oficiales. También te

gustaría verlo muerto. Matarás a veinte de ellos y otros veinte saldrán en su

lugar. Simplemente apesta en las fosas nasales.

Has venido a despreciar a esa generación mayor que te

envió a esta locura, a esta cámara de tortura. A tu alrededor, tus compañeros

están muriendo. Muriendo de heridas abdominales, amputaciones dobles, caderas

destrozadas, y piensas: "Sólo tengo veinte años, pero soy capaz de matar a

cualquiera. Incluso a mi padre si se me acerca".

Ayer, trataste de salvar a un perro mensajero herido,

y alguien gritó: "No seas tonto". Un soldado está gorgoteando a tus

pies. Le apuñalaste con una daga en el estómago, pero el hombre todavía vive.

Sabes que deberías terminar el trabajo, pero no puedes. Te han clavado en la

cruz y un soldado romano está poniendo una esponja de vinagre en tus labios.

Los meses pasan. Te vas a casa con un permiso. No

puedes comunicarte con tu padre. Él dijo: "Serás un cobarde si no te

enrolas". Tu madre también, al salir de la puerta, dice: "Ten cuidado

con las chicas francesas". Más locura. Luchas durante una semana o un mes

y avanzas diez yardas. Y al mes siguiente las vuelves a perder.

Toda esa cultura de hace mil años, esa filosofía, esa

sabiduría -Platón, Aristóteles, Sócrates- ¿qué le sucedió? Debería haber

evitado todo esto. Tus pensamientos te devuelven a casa. Y una vez más eres un

colegial que camina entre los altos álamos. Es un recuerdo agradable. Más

bombas cayendo sobre ti desde dirigibles. Tienes que hacerlo ahora. Ni siquiera

puedes mirar a nadie por miedo a algo impredecible que podría suceder. La tumba

común. No hay otras posibilidades.

Entonces notas las flores de la cereza, y ves que a

la naturaleza no le afecta todo esto. Los álamos, las mariposas rojas, la

belleza frágil de las flores, el sol - se ve cómo la naturaleza es indiferente

a todo. Toda la violencia y el sufrimiento de toda la humanidad. La naturaleza

ni siquiera lo nota.

Estás tan solo. Entonces un pedazo de metralla golpea

el lado de su cabeza y estás muerto. Has sido descartado, tachado. Has sido

exterminado. Dejé este libro y lo cerré. Nunca quise volver a leer otra novela

de guerra, y nunca lo hice.

Charlie Poole de Carolina del Norte tenía una canción

que conectó con todo esto. Se llama "No me estás hablando", y las

letras son así:

Vi un cartel en una ventana caminando por la ciudad

un día. Únete al ejército, 'ven a ver el mundo' es lo que tenía que decir.

Verás lugares emocionantes con una tripulación jovial, conocerás gente

interesante y aprenderás a matarlos también. Oh no me estás hablando a mí, no

me estás hablando a mí. Puedo estar loco y todo eso, pero soy sensato. No me

estás hablando a mí, no me estás hablando a mí. Matar con una pistola no suena

divertido. No me estás hablando a mí.

'La Odisea' es un gran libro cuyos temas han influido

en las baladas de muchos compositores: 'Homeward Bound', 'Green on Grass

Range', 'Home on the Range' y mis canciones también.

'La Odisea' es una historia

extraña y aventurera de un hombre adulto que trata de llegar a casa después de

luchar en una guerra. Un largo viaje a casa lleno de

trampas y trampas. Su maldición es vagar para siempre. Siempre tiene que volver

al mar por algún motivo. Grandes trozos de rocas hacen oscilar su bote. Hace

enfadar a gente a la que no debería. Hay gente problemática en su tripulación.

Traición. Sus hombres se convierten en cerdos y luego se convierten en hombres

más jóvenes y más guapos. Siempre está tratando de rescatar a alguien. Es un

hombre viajero, pero está haciendo demasiadas paradas.

Atrapado en una isla desierta. Encuentra cuevas

desiertas y se esconde en ellas. Se encuentra con gigantes que dicen: "Te

comeré esta vez". Y se escapa de los gigantes. Trata de regresar a casa,

los vientos le llevan de un lado a otro. Vientos intranquilos, vientos fríos,

vientos hostiles. Viaja lejos y los vientos lo alejan más.

Siempre le advierten de las cosas por venir. Tocando

cosas que le dijeron que no lo hiciera. Hay dos caminos por recorrer, y ambos

son malos. Ambos peligrosos. En uno se podría ahogar y por el otro se podría

morir de hambre. Entra en los estrechos estrechos con espumosos remolinos que

lo tragan. Se reúne con monstruos de seis cabezas con colmillos afilados. Los

rayos le atacan. Dioses y dioses lo protegen, pero otros quieren matarlo.

Cambia identidades. Está agotado. Se duerme y se despierta por el sonido de la

risa. Él cuenta su historia a extraños. Han pasado veinte años. Lo llevaron a

algún lugar y se fue de allí. Las drogas cayeron en su vino. Ha sido un camino

demasiado duro.

De muchas maneras, algunas de estas mismas cosas te

han pasado. Tú también has compartido cama con la mujer equivocada. También has

sido hechizado por voces mágicas, voces dulces con extrañas melodías. También

has llegado demasiado lejos. Y también has tenido llamadas cercanas. Has

enojado a la gente que no deberías. Y has sentido que el viento enfermo, el que

te sopla en la cara, no es bueno. Y eso no es todo.

Cuando vuelve a casa, las cosas no son mejores. Los

sinvergüenzas se han mudado y están aprovechando la hospitalidad de su esposa.

Y hay demasiados. Y aunque es más grande que todos y el mejor en todo - mejor

carpintero, mejor cazador, mejor experto en animales, mejor marinero - su valor

no lo salvará, pero su truco lo hará.

Todos estos rezagados tendrán que pagar por profanar

su palacio. Se disfrazará como un mendigo sucio, y un humilde criado le dará

patadas por los escalones con arrogancia y estupidez. La arrogancia del siervo

le revuelve, pero él controla su ira. Él es uno contra cien, pero todos caerán,

incluso los más fuertes. No era nadie. Y cuando todo está dicho y hecho, cuando

él finalmente está en casa, él se sienta con su esposa. Y le cuenta historias.

Entonces, ¿qué significa todo ésto? Yo y muchos otros

compositores han sido influidos por estos mismos temas. Y pueden significar

muchas cosas diferentes. Si una canción te mueve, eso es todo lo que importa.

No tengo que saber lo que significa una canción. He escrito todo tipo de cosas

en mis canciones. Y no voy a preocuparme por eso, lo que significa todo. Cuando

Melville puso el Antiguo Testamento, referencias bíblicas, teorías científicas,

doctrinas protestantes y todo ese conocimiento del mar y de los veleros y las

ballenas en una sola historia, no creo que tampoco se preocupara por lo que significa

.

John Donne, el poeta-sacerdote que vivió en la época

de Shakespeare, escribió estas palabras, "El Sestos y Abydos de sus

pechos. No de dos amantes, sino de dos amores, de los nidos". Yo tampoco

sé lo que significa. Pero suena bien. Y quieres que tus canciones suenen bien.

Cuando Ulises en 'La Odisea' visita al famoso

guerrero Aquiles en el inframundo - Aquiles, que cambió una larga vida llena de

paz y alegría por una corta cargada de honor y gloria - le dice a Odiseo que

todo fue un error. "Acabo de morir, eso es todo." No había honor.

Ninguna inmortalidad. Y si pudiera, elegiría regresar y ser un esclavo humilde

de un arrendatario en la tierra en lugar de ser lo que es -un rey en la tierra

de los muertos- que cualesquiera que fueran sus luchas de vida, eran

preferibles A estar aquí en este lugar muerto.

Eso es lo que son las canciones también. Nuestras

canciones están vivas en la tierra de los vivos. Pero las canciones son

diferentes a la literatura. Están destinadas a ser cantadas, no leídas. Las

palabras en las obras de Shakespeare estaban destinadas a actuar en el

escenario. Así como las letras de las canciones están destinadas a ser

cantadas, no a leerse en una página. Y espero que algunos de ustedes tengan la

oportunidad de escuchar estas letras de la forma en que fueron destinados a ser

escuchadas: en vivo o en un disco, y sin embargo la gente está escuchando

canciones estos días. Regreso una vez más a Homero, quien dice: "Canta en mí, oh Musa, y a través de mí cuenta la

historia".

COMENTARIO AL DISCURSO DEL NOBEL DE BD

ResponderEliminarA última hora leí este ensayo de auto-biografía artística y escuché sin moverme de mi silla el audio de 27 minutos, -con suave música de fondo de piano- , que Bob Dylan ha enviado a la Academia Sueca.

Tal vez, -como nos confiesa al principio- , para reflexionar sobre la relación entre canciones y literatura. Tal vez para desafiar a sus detractores o a sus no-fans declarando a su manera sinuosa, en parábolas, con una voz todavía muy bella e infinitamente matizada (de hecho, se podría decir que canta o sostiene una melodía en ciertos momentos de su discurso, como cuando cita una canción ajena) que sí, que acepta el premio y que quizás se lo merece más que Murakami, más que Adonis y más que nadie : Porque él es el Homero de nuestros tiempos, el testigo de la pasión del Capitán y la Ballena y el soldado aterrorizado en las trincheras alambradas de la PGM.

Porque en él, en Dylan, "canta la Musa y se cuenta la Historia".

-

COMENTARIO AL DISCURSO DEL NOBEL (Continuación)

ResponderEliminar¿O quizás es que sigo endiosando a mi ídolo? -"...Look the parkingmeters/ don´t follow leaders"- Él solo me da alegrías y confianza en la vida desde su distancia. Pero a lo peor ha escrito su "Lecture" solo por pasta, y no por razones poéticas ni amorosas. Es lo que piensa la mayoría de comentaristas políticos de la tele y la radio: Que a última hora el codicioso sionista y ex-yonqui Zimmerman ha terminado como un mal estudiante el trabajillo obligatorio que exigen los suecos para que no quitarle el premio. - Pero, en realidad, desestimo y no acabo de creerme la motivación de la avaricia.

Una vez más Dylan me tocó el corazón y me arrancó las lágrimas con lo que decía.

Se ha llegado a saber que el Maestro BD tras conocer la notica del premio y dar algunos conciertos en los que no hizo la mínima mención a su suceso, se retiró de la carretera y de la gira y anduvo unas semanas perdido en los bosques. Al parecer BD, de vez en cuando necesita dormir en una tienda de campaña o debajo de un árbol. Suele internarse a caballo en lo más profundo de los más profundos bosques o en barca por ríos u océanos tristes donde nadie le reconocerá porque apenas hay seres humanos. Y si no, se adentra en la boca de una mina abandonada.

Se cuenta que esta vez se marchó haciendo autoestop y disfrazado de viejo mendigo hasta la selva de Helvétière (en Minnesotta pero ya muy próxima al Canadá). Le llevaron hasta allí unos descendientes de antiguos leñadores a los que les compró un caballo con el que desapareció entre los árboles sin caminos. - Durante cinco días no le volvieron a ver.

"Pero cuando regresó Mr. Dylan parecía otro hombre", comenta impresionado uno de los operarios. "Él no nos dijo nada. Sonreía con amabilidad y de noche, con un par de whiskies de los nuestros encima, hasta nos cantaba canciones de la guerra de Secesión y de la Conquista del Oeste. No entiendo cómo un ser humano puede saber tantas canciones ni cómo puede albergar tanto en su cabeza. Se sabía cánticos de los sioux y de los vikingos de Groenlandia. Así que nos lo pasábamos en grande con Bob. Pero aunque siempre nos diese alegrías, estaba claro que le había pasado algo en La Hélvètière aunque no nos lo contase y cada día se inventara una historia distinta, más inverosímil que el anterior parea responder a nuestras preguntas: en una de sus versiones unos extra-terrestres le habían abducido en el Mayflower; en otra, el mismo Elías bajándose de su carro de fuego había cocinado para él pan ácimo. Yo lo que creo es que se había encontrado con Nuestro Señor Jesucristo, el de verdad, y que Dios nuestro Señor le había hablado a Bob .

"Luego Bob, en cuanto estuvo un poco más repuesto se marchó casi llorando, en silencio pero mirándonos con ojos húmedos y con mucho... con mucho amor. La verdad yo soy un simple leñador y creo que es la primera vez que uso esta palabra en mi vida."

COMENTARIO AL DISCURSO DEL NOBEL (Continuación de la continuación)

ResponderEliminarEstos que aquí reproduzco en su versión original (traducción dudosa y con errores incluida; ni siquiera cito de quién) son los resultados de esa meditación solitaria en la selva. Creo que merecen ser leídos, sentidos y meditados. No es una redacción de circunstancias para embolsarse casi un millón de euros. es la última obra genial e imprevista de un genio.

-En sintonía con las afirmaciones del Maestro, animo a todos los que lean esto a no conformarse con la letra y escuchar la grabación original (accesible online), la voz del Dylan de 2017, el de siempre, recitando, intentando articular en español la jota de "Don Quihoute" o emocionándose o acelerando el ritmo a voluntad. Mejor oírlo que leerlo. Pues igual que las canciones, igual que la Odisea, igual que las grandes obras de teatro, este discurso no fue pensado para ser leído sino para ser escuchado.

Con estas tranquilas rememoraciones del abuelete Dylan sobre sus influencias, el pequeño Gigante había vuelto a hacer algo inusitado, algo polémico, algo que nadie había hecho antes. Algo incomprensible.

(Pues la verdad es que sigo sin entender en absoluto las palabras y los gestos de Dylan después de intentarlo desde hace casi 40 años; confieso que en última instancia tampoco sé qué ha querido decir con este último mensaje; y lo habré leído más de 7 veces; -quizás debo releerlo 70 veces 7 para vislumbrar su significado. Quizás de dylanita debería pasar a convertirme en dylanólogo... ¿Qué había querido decir el daimon de Dylan al contar de nuevo la historia de su encuentro único y mágico con Budy Holly, al transformar Moby Dick en una "dylanesque", Sin Novedad en el Frente en una ácida canción protesta de las suyas? ¿Quería decir que el autor daba igual, que lo importante era cantar y contar la historia? ¿Quería decir que la literatura del siglo XXI iba a volver a sus raíces, a la música como lo fue en los tiempos micénicos? )

(Tal vez. En el cerebro de Dylan podías encontrarte cualquier cosa, posibilidades que, desde nuestras capacidades inferiores, no podemos ni imaginarnos: Bob Dylan en el curso de una entrevista, había llegado a demostrar que una silla era un objeto absolutamente

místico ).

Por eso, aunque no es habitual en el blogethicayphilosophia no me he quedado tranquilo hasta no ver publicada íntegra y textual su extraña relación con la Poesía y con la Música, tal como nos la cuenta, dulce y expresivo, a los que llevamos mucho tiempo enamorados. Y Homero nos parece a su lado un bardo primitivo. Y Herman Melville un escritor muy inferior a Bob Dylan. Por eso reproduzco un texto ajeno por una vez y no material propio.

Su voz casi llorosa, implorante cuando pronuncia las palabras finales ("Canta en mí, oh Musa, y a través de mí cuenta la historia•": "Sing in me, oh Muse and through me tell the story!") no hace

más que engrandecer su leyenda. -Dylan es el Norte de la humanidad y parece incapaz de decepcionarnos. Que Dios le bendiga.